Warhammer Red Thirst Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

The Dark Beneath the World by William King

The Spells Below by Neil Jones

The Light of Transfiguration by Brian Craig

The Song by Steve Baxter

The Voyage South by Nicola Griffiths

THE OLD WORLD TIMELINE

A brief guide to the history of the Warhammer World

Contents

Red Thirstby Jack Yeovil

The Dark Beneath the Worldby William King

The Spells Belowby Neil Jones

The Light of Transfigurationby Brian Craig

The Songby Steve Baxter

The Voyage Southby Nicola Griffiths

RED THIRST

by Jack Yeovil

Eventually, Vukotich was awoken by the steady rumbling of the wheels and the clatter of the chains. It was dark inside the closed wagon, but he could tell from the bumpy ride that they weren't in Zhufbar any more. A paved road within the walls of the city wouldn't be as bumpy as this. They were being taken up into the mountains.

He smelled his travelling companions well before his eyes got used enough to the gloom to make out their shapes. There were too many of them to be comfortably confined in the space available, and, despite the mountain cool outside, it was uncomfortably hot. Nobody said anything, but the chains clanked as the wagon lurched over obstacles or swayed from side to side. Someone started wailing, but someone else cuffed him soundly and he shut up.

Vukotich could still feel the blow that had knocked him out. An Acolyte of the Moral Crusade had bludgeoned him with his blessed iron during the arrest, and he supposed from the pains in his chest and legs that the Guardians of Purity had taken the opportunity to kick him thoroughly when he was unconscious. Glinka's blackhood bastards might not be much when it came to knocking back the juice or groping the girls, but they were certainly unequalled champions of unnecessary violence. He only wished he'd been awake when the Company of Killjoys reached for their skullbreakers. He'd been through enough campaigns to learn a little about self-defence.

Like everyone else, Vukotich hadn't at first taken Claes Glinka seriously. He had been hearing a lot lately about this cleric who adhered to no particular god, but called himself the Guardian of Morality, and preached fiery sermons in rural town squares against lasciviousness, in favour of the sanctity of marriage and lamenting the decline of the Empire's moral values. For Glinka, all the things a man might take pleasure in were steps on the Road to Chaos and Damnation. Then, so swiftly that most people barely had time to react, Claes Glinka had won some measure of Imperial Approval and was the figurehead of a sizeable movement. His Crusade swept through the Old World from town to town, from city to city. In Nuln, he had managed to get the university authorities to close down the Beloved of Verena, a brothel that had been serving the students and lecturers of the city since the days of Empress Agnetha. In the Sudenland, he had supervised the destruction of the fabulously-stocked wine cellars of the Order of Ranald, and seen to the burning of that region's famous vineyards. His agitators worked in the councils of the rulers to change the laws, to enforce prohibitions against strong drink, public and private licentiousness, even sweetmeats and tobacco. Many resisted, but a surprising number, frequently those most known for their own personal laxity, caved in and let Glinka have his way.

Vukotich tested his shackles. His feet were chained to a bar that ran the length of the wagon, inset into the floor. His hands were in manacles, stringing him between the prisoners either side of him. He felt like a trinket on a memento bracelet. The smell got worse as the journey progressed. The wagon made no latrine stops, and some of the prisoners didn't have Vukotich's self-control.

He had come to the fortress city in search of work. His last employment had ended with the rout of Vastarien's Vanquishers by the bandits of Averland. Upon the death of Prince Vastarien, he became free to pledge his sword-arm to another employer, and he had hoped to find a suitable position with one of the warrior aristocrats attending the Festival of Ulric in Zhufbar. The Festival, dedicated to the God of Battle, Wolves and Winter, took place each autumn, to celebrate the onset of winter, and was held in a different city every year. This was where the campaigns against the creatures of darkness were planned, where the arrangements for the defence of the Empire were made, and where the disposition of Emperor Luitpold's forces was decided. It was also the best place for a masterless mercenary to come by a position.

The boards of the wagon's roof were ill-fitting, and shafts of sunlight sliced down into the dark, allowing him to see something of his companions. Everyone was in chains, their feet shackled to the central bar. Most of them had obvious bludgeon wounds. To his left, stretching the chain between their wrists to its utmost, was a fellow with the oiled ringlets of a nobleman of Kislev, dressed only in britches that had been put on back to front. He was in a silent rage, and couldn't stop trembling. Vukotich guessed he would rather have remained in whoever's bed he had been hauled from. An old woman in well-worn but clean clothes wept into her hands. She was repeating something, over and over, in a steady whine. "I've been selling herbs for years, it's not against the law." Several others were long-term boozers, still snoring drunkenly. He wondered how they'd react when they found out they were about to take the Cure in a penal colony. All human misery was here. And the misery of several of the other higher races too. Opposite were three dwarfs, roped together and complaining. They poked at each other's eyes and grumbled in a language Vukotich didn't know.

Zhufbar had been different this time. Claes Glinka was in town, and had gained the ear of the fortress city's Lord Marshal, Wladislaw Blasko. There were posters up all over the streets, announcing strict laws against gambling, drinking, brawling, dancing, "immodest" music, prostitution, smoking in public and the sale of prohibited stimulants. Vukotich had laughed at the pompously-phrased edicts, and assumed they were all for show. You couldn't hold a Festival for the God of Battle and expect a cityload of off-duty soldiers not to spend their time dicing, getting drunk, fighting, partying, chasing whores, or chewing weirdroot. It was just ridiculous. But the black-robed Acolytes were everywhere. In theory, they were unarmed, but the symbol Glinka had chosen for the Crusade was a two-foot length of straight iron carved with the Seven Edicts of Purity, and those were well in evidence whenever the Guardians attempted to enforce the new laws. On his first morning in the city, Vukotich saw three hooded bullyboys set upon a street singer and batter the lad senseless with their iron bars. They trampled his mandolin to pieces and dragged him off to the newly-dedicated Temple of Purity. Where before there had been ale-holes and tap-rooms, there were now Crusade-sanctioned coffee houses, with in-house preachers replacing the musicians and cold-faced charity collectors rather than welcoming women. On his last visit, Vukotich had found it impossible to walk down the city's Main Gate Road without being propositioned by five different whores, offered a chew of weirdroot for five pfennigs, and hearing twelve different types of street singer and musician competing for his attention. Now, all he found were tiresome clerics droning on about sin, and Moral Crusaders rattling collection tins under his nose.

The prisoner shackled to his right hand was a woman. He could distinguish her perfume amid the viler odours of the other convicts. She sat primly, knees together, back straight, looking more fed up than desperate. She was young and dressed in immodestly thin silks. Her hair was elaborately styled, she wore a deal of cheap jewellery and her face was painted. Something about the set of her features struck him as predatory, tenacious, hungry. A whore, Vukotich supposed. At least a third of the convicts in the wagon were obvious prostitutes. Glinka's Crusade was especially hard on them.

The first day

of the festival had been fine. He had attended the Grand Opening Ceremony, and listened to the speeches of the visiting dignitaries. The Emperor was represented by no less a hero than Maximilian von Konigswald, the Grand Prince of Ostland, whose young son Oswald had recently distinguished himself by vanquishing the Great Enchanter, Constant Drachenfels. After the ceremony, he had found himself at a loose end. Later in the week, he would learn which generals were hiring. But now, everyone was busy renewing old friendships and looking for some entertainment. Vukotich had fallen in with Snorri, a half-Norse Cleric of Ulric he had served with during his time defending Erengrad from the trolls, and they had toured the hostelries. The first few houses they visited were deadly dull, with apologetic innkeepers explaining that they were forbidden by law to serve anything other than near beer and watered-down wine and then only for an absurdly brief given period each evening. There were always hooded Acolytes sitting in the corner to make sure the taverners obeyed Glinka's edicts.

As they stormed out of the third such place, a small fellow with a black feather in his cap sidled up to them and offered, for a fee, to guide them to an establishment that cared little for the Crusade and its restrictions. They haggled for a while, and finally handed over the coin, wherupon Blackfeather led them through a maze of alleyways in the oldest part of the city and down into some disused defence tunnels. Zhufbar had been a dwarfish city originally, and the Norseman had to bend over double to get through the labyrinth. They heard noisy music and laughter up ahead, and their hearts warmed a little. Apart from anything else, they'd be able to stand up straight. It turned out to be a "Flying Inn," a revelry that moved from place to place two steps ahead of the Crusade. Tonight, it was in an abandoned underground armoury. A band of elven minstrels were playing something good and loud and raucous, while their admirers chewed weirdroot to better appreciate the music. Blackfeather offered them dried lumps of the dream-drug, and Snorri shoved one into his mouth, surrendering to the vividly-coloured dreams, but Vukotich declined, preferring to sample the strong black ale of the city. Girls wearing very little were dancing upon a makeshift stage while coloured lanterns revolved and different varieties of scented smoke whirled. Huge casks were being tapped and the wine was flowing freely, dicers and card-players were staking pouches of coins, and a dwarf jester was making a series of well-appreciated lewd jokes about Glinka, Blasko and various other leading lights of the Moral Crusade. Someone somewhere was making a lot of money from the "Flying Inn." Of course, Vukotich had barely drained his first tankard and started looking around for a spare woman when the raid started...

And here he was, in chains, bound for some convict settlement in the mountains. He knew they'd put him to work in some hell-hole of a mine or a quarry and that he'd probably be dead within five years. He cursed all Guardians of Morality, and rattled his chains.

For once, he had a stroke of luck. His left manacle was bent out of shape, its rivets popped. He slipped his hand free.

Now, when the wagon stopped, he would have a chance.

Once they were out of the city, Dien Ch'ing felt free to pull off his black steeple-hood. This far to the west, the people of Cathay were uncommon enough to attract attention, and so the Order's face-covering headgear was a convenient way of walking about unquestioned. The round-eyed, big-nosed, abnormally-bearded natives of this barbarous region were superstitious savages, ignorant enough to suppose that his oriental features were marks of Chaos and toss him into the nearest bonfire. Of course, in his case, they wouldn't have been entirely unjustified. All who ascended the Pagoda of Tsien-Tsin, Lord of the Fifteen Devils, Master of the Five Elements, had more than a trace of the warpstone in their blood.

A few too many clashes with the Monkey-King's warrior monks had forced him to leave the land of his birth, and now he was a wanderer across the face of the world, a servant of Tsien-Tsin, an unaltered Acolyte of Chaos, a Master of the Mystic Martial Arts. He had been shepherded through the Dark Lands by the Goblin Lords, and conveyed across the Worlds' Edge mountains to the shores of the Blackwater. There was an Invisible Empire in the Known World, an empire that superseded the petty earthly dominions of the Monkey-King, the Tsar of Kislev or the Emperor Luitpold. This was the empire of the Chaos Powers, of Khorne and Nurgle in the west and north, and of Great Gojira and the Catshit Daemons in the east. Tsien-Tsin, the Dark Lord to whom he pledged his service, was known here as Tzeentch. The proscribed cults of Chaos flourished, and the warp-altered horde grew in strength with each cycle of the moons. The kingdoms of men squabbled, and the Invisible Empire grew ever more powerful.

They made slow progress up into the mountains. Ch'ing sat on his padded seat beside the driver of the second wagon. He was impatient to get this coffle to the slave-pits, and be back about his business in Zhufbar. He had made this run many times, and it was becoming boring. Once they reached the secret caves where the goblins waited, the convicts would be seperated into three groups. The young men would be taken off to work in the warpstone mines of the Dark Lands, the young women sold to the slave markets of Araby, and the remainder slaughtered for food. It was a simple business, and it served the Powers of Chaos well. Always, he allowed the goblins to pick out a woman or two, or perhaps a comely youth, and watched them at their sport. Claes Glinka would be shocked at the ultimate fate of those whose sins he abhorred. Ch'ing laughed musically. It was most amusing.

But this was not the time for amusements. There was important business to be transacted at the Festival of Ulric. There were many high-ranking Servants of Chaos in the city, and they too were plotting strategy. When Ch'ing had been visited in the Dark Lands by Yefimovich, the Kislevite High Priest of Tzeentch, he had been told that the dread one wished him to take a position within the Moral Crusade and do his best to turn Glinka's followers into an army for the advancement of Chaos. Thus far, his subtle strategies had worked well. The Crusade hoods could conceal more than slanted eyes, and Ch'ing knew that many an iron-carrying Acolyte bore the marks of the warpstone under his mask. Glinka was a blind fanatic, and easily duped. Sometimes, Ch'ing wondered whether the Guardian of Morality had not made his own dark bargain with the Invisible Empire. No one could put aside so many pleasures without a good reason. However, Glinka was just as likely sincere in his passions. All western barbarians were mad to some extent. Ch'ing wondered what it must be like to fear one's own appetites so much that one sought to suppress the pleasures of all the world. To him, thirsts existed to be slaked, lusts to be satiated, desires to be fulfilled.

The sun was full in the sky now. The coffle had been on the road all night. Most of the convicts would still be asleep, or nursing their hangovers. There were three wagons in all, and although the drivers were used to the mountain roads, progress was still frustratingly snail-like. Just now, they were on a narrow ledge cut into a steep, thickly forested incline. Tall evergreens rose beside the path, their lowest branches continually striking the sides of the wagons. There were bandits in the mountains, and worse things, altered monstrosities, renegade dwarf bands, Black Orcs, Skaven, amphisbaenae, mountain bears. But he took comfort; there was unlikely to be anything worse out there than himself. His position on the Pagoda gave him the power to summon and bind daemons, to tumble through the air in combat, and to fight for a day and a night without breaking a sweat.

The first wagon halted, and Ch'ing nudged the driver beside him to rein in the horses. The animals settled. Ch'ing waved to the third wagon, which also creaked to a stop.

"Tree down ahead, master," shouted the Acolyte on the first wagon. Ch'ing sighed with irritation. He could use a simple spell to remove the obstacle, but that would drain him, and he knew the Blessings of Tsien-Tsin would be required soon for other purposes. There was nothing for it but to use the available tools.

Holding his robes about him, he stepped down to the road.

He had to be careful of his footing. It would be easy to take a fall, and wind up bent around a tree hundreds of feet below. The mightiest of warrior magicians alw

ays met their deaths through such small missteps. It was the gods' way of keeping their servants humble.

He walked round to the back of the wagon, and unlocked the door. The foul stench of the prisoners wafted out, and he held his nose. Westerners always smelled vile, but this crew were worse than usual.

The convicts cringed away from the light. He knew some of them would be startled by his Celestial face. So be it. They were in no position to be offended.

"Attention," he said. "Those of you who do not assist us in the removal of the tree that blocks our path will have their ears severed. Volunteers?"

The driver yanked at the chain threaded around the central bar of the wagon, and took out the keys. Guards with whips and swords clustered around the wagon. Ch'ing stood back. The central bar was raised, and the convicts were hauled out, their ankle-shackles pulling off the bar like beads from a string. Their feet were free, but they would still be chained wrist to wrist.

First out was the fragile girl he had been warned against. She didn't like the strong sunlight, and covered her eyes. After her was a sturdy young man with more than a few battle scars. Vukotich, he knew. One of the mercenaries. Then, there was a pause, as the half-naked Pavel Alexei hesitated on the lip of the wagon.

Something was wrong.

The whore and the mercenary were shackled together, and the man held his arm up awkwardly, as if chained to the degenerate. But the Kislevite was pressing his hand to his forehead, an empty manacle dangling from his wrist.

Two of the prisoners were loose from the chain.

The mercenary looked him in the eyes, and Ch'ing saw defiance and hatred reflected at him.

He had his hand on his scimitar-handle, but the mercenary was fast.

The Red Feast - Gav Thorpe

The Red Feast - Gav Thorpe The Siege of Greenspire - Anna Stephens

The Siege of Greenspire - Anna Stephens Fangs of the Rustwood - Evan Dicken

Fangs of the Rustwood - Evan Dicken Blacktalon - When Cornered - Andy Clark

Blacktalon - When Cornered - Andy Clark Acts of Sacrifice - Evan Dicken

Acts of Sacrifice - Evan Dicken Obsidian - David Annandale

Obsidian - David Annandale A Dirge of Dust and Steel - Josh Reynolds

A Dirge of Dust and Steel - Josh Reynolds The Sands of Grief - Guy Haley

The Sands of Grief - Guy Haley The Book of Transformations - Matt Keefe

The Book of Transformations - Matt Keefe Warriors of the Chaos Wastes - C L Werner

Warriors of the Chaos Wastes - C L Werner Strong Bones - Michael R Fletcher

Strong Bones - Michael R Fletcher Sepulturum - Nick Kyme

Sepulturum - Nick Kyme The Witch Takers - C L Werner

The Witch Takers - C L Werner Gotrek & Felix- the Third Omnibus - William King & Nathan Long

Gotrek & Felix- the Third Omnibus - William King & Nathan Long A Tithe of Bone - Michael R Fletcher

A Tithe of Bone - Michael R Fletcher Reflections in Steel - C L Werner

Reflections in Steel - C L Werner Masters of Stone and Steel - Gav Thorpe & Nick Kyme

Masters of Stone and Steel - Gav Thorpe & Nick Kyme Gotrek & Felix- the Second Omnibus - William King

Gotrek & Felix- the Second Omnibus - William King Valdor- Birth of the Imperium - Chris Wraight

Valdor- Birth of the Imperium - Chris Wraight The Bone Cage - Phil Kelly

The Bone Cage - Phil Kelly Gotrek & Felix- the First Omnibus - William King

Gotrek & Felix- the First Omnibus - William King The Dance of Skulls - David Annandale

The Dance of Skulls - David Annandale Gloomspite - Andy Clark

Gloomspite - Andy Clark The Deeper Shade - C L Werner

The Deeper Shade - C L Werner Spear of Shadows - Josh Reynolds

Spear of Shadows - Josh Reynolds Gotrek - One, Untended - David Guymer

Gotrek - One, Untended - David Guymer Gotrek & Felix- the Fourth Omnibus - Nathan Long

Gotrek & Felix- the Fourth Omnibus - Nathan Long Gods' Gift - David Guymer

Gods' Gift - David Guymer Blood Gold - Gav Thorpe

Blood Gold - Gav Thorpe Slaves to Darkness 03 (The Heart of Chaos)

Slaves to Darkness 03 (The Heart of Chaos) Hamilcar- Champion of the Gods - David Guymer

Hamilcar- Champion of the Gods - David Guymer Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood And Steel)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood And Steel) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (what price vengeance)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (what price vengeance) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood of the Dragon)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood of the Dragon) Ursuns Teeth

Ursuns Teeth The Blackhearts Omnibus (Tainted Blood)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (Tainted Blood)![Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/09/daemon_gates_trilogy_01_day_of_the_daemon_preview.jpg) Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon]

Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon] The Blackhearts Omnibus (The Broken Lance)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (The Broken Lance) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood Money)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood Money) The Blackhearts Omnibus (Hetzaus Follies)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (Hetzaus Follies) Warhammer Red Thirst

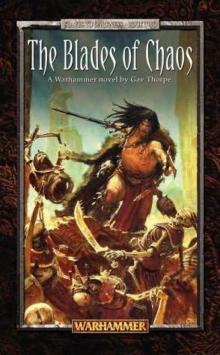

Warhammer Red Thirst Slaves to Darkness 02 (The Blades of Chaos)

Slaves to Darkness 02 (The Blades of Chaos)