The Red Feast - Gav Thorpe

The Red Feast - Gav Thorpe The Siege of Greenspire - Anna Stephens

The Siege of Greenspire - Anna Stephens Fangs of the Rustwood - Evan Dicken

Fangs of the Rustwood - Evan Dicken Blacktalon - When Cornered - Andy Clark

Blacktalon - When Cornered - Andy Clark Acts of Sacrifice - Evan Dicken

Acts of Sacrifice - Evan Dicken Obsidian - David Annandale

Obsidian - David Annandale A Dirge of Dust and Steel - Josh Reynolds

A Dirge of Dust and Steel - Josh Reynolds The Sands of Grief - Guy Haley

The Sands of Grief - Guy Haley The Book of Transformations - Matt Keefe

The Book of Transformations - Matt Keefe Warriors of the Chaos Wastes - C L Werner

Warriors of the Chaos Wastes - C L Werner Strong Bones - Michael R Fletcher

Strong Bones - Michael R Fletcher Sepulturum - Nick Kyme

Sepulturum - Nick Kyme The Witch Takers - C L Werner

The Witch Takers - C L Werner Gotrek & Felix- the Third Omnibus - William King & Nathan Long

Gotrek & Felix- the Third Omnibus - William King & Nathan Long A Tithe of Bone - Michael R Fletcher

A Tithe of Bone - Michael R Fletcher Reflections in Steel - C L Werner

Reflections in Steel - C L Werner Masters of Stone and Steel - Gav Thorpe & Nick Kyme

Masters of Stone and Steel - Gav Thorpe & Nick Kyme Gotrek & Felix- the Second Omnibus - William King

Gotrek & Felix- the Second Omnibus - William King Valdor- Birth of the Imperium - Chris Wraight

Valdor- Birth of the Imperium - Chris Wraight The Bone Cage - Phil Kelly

The Bone Cage - Phil Kelly Gotrek & Felix- the First Omnibus - William King

Gotrek & Felix- the First Omnibus - William King The Dance of Skulls - David Annandale

The Dance of Skulls - David Annandale Gloomspite - Andy Clark

Gloomspite - Andy Clark The Deeper Shade - C L Werner

The Deeper Shade - C L Werner Spear of Shadows - Josh Reynolds

Spear of Shadows - Josh Reynolds Gotrek - One, Untended - David Guymer

Gotrek - One, Untended - David Guymer Gotrek & Felix- the Fourth Omnibus - Nathan Long

Gotrek & Felix- the Fourth Omnibus - Nathan Long Gods' Gift - David Guymer

Gods' Gift - David Guymer Blood Gold - Gav Thorpe

Blood Gold - Gav Thorpe Slaves to Darkness 03 (The Heart of Chaos)

Slaves to Darkness 03 (The Heart of Chaos) Hamilcar- Champion of the Gods - David Guymer

Hamilcar- Champion of the Gods - David Guymer Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood And Steel)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood And Steel) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (what price vengeance)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (what price vengeance) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood of the Dragon)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood of the Dragon) Ursuns Teeth

Ursuns Teeth The Blackhearts Omnibus (Tainted Blood)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (Tainted Blood)![Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/09/daemon_gates_trilogy_01_day_of_the_daemon_preview.jpg) Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon]

Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon] The Blackhearts Omnibus (The Broken Lance)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (The Broken Lance) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood Money)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood Money) The Blackhearts Omnibus (Hetzaus Follies)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (Hetzaus Follies) Warhammer Red Thirst

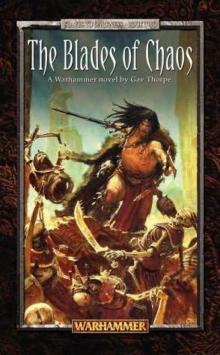

Warhammer Red Thirst Slaves to Darkness 02 (The Blades of Chaos)

Slaves to Darkness 02 (The Blades of Chaos)