The Sands of Grief - Guy Haley Read online

Page 2

Shattercap dipped his pink tongue into the glass. When it touched the blessed water, he let out a relieved sigh.

‘It tastes of the forests. It tastes of the rivers and the seas. It tastes of home!’

Maesa set Shattercap down and wet his own lips with the water. His skin tingled. His face glowed with renewed life, and the dark rings faded. He dabbed a little on his forefinger, to rub on the gums of the sleeping stag, then corked the flask and put it away.

A miserable moaning sang out of the night.

‘Best keep this out of sight,’ Maesa said. ‘The dead here are cold, and will seek out a source of life such as this.’

They went further edgewards, heading away from the heartlands of Shyish. At night, the dark was full of desperate howls. Cold winds blew, carrying whispers that chilled the marrow. Thunderous storms cracked the sky with displays of purple lightning. No rain fell. Nothing lived. The days grew shorter with every league they went, the sun paler, until they passed some fateful meridian, and went into lands clothed perpetually in shadow.

Where the light died, the sky changed. Beneath amethyst chips of stars a new desert began. Zircona was a wasteland, but it was part of a living world. This new desert was wholly a dead place.

Maesa slipped from Aelphis’ saddle.

‘We have reached the Sands of Grief. Now is the time for the magic of Throck and Grimmson,’ he said. He took out the gold compass, and set it on a stone. From a velvet bag he removed the skull of Ellamar and unwound its wrappings, set it on the ground, and knelt beside it.

‘Forgive me, my love,’ he said. Delicately, he took up the brown skull, and pinched a tooth between forefinger and thumb. ‘I apologise for this insult to your remains. I shall replace it with the brightest silver.’

Grimacing at what he must do, he drew the tooth. It came free with a dry scraping.

He set the tooth aside, rewrapped his precious relic, and returned it to the back of his saddle. Then he opened up the lid of the compass-box and placed the tooth within.

‘Let us see if it works.’

He held the compass up to his face.

Slowly, the pointer swung about, left, then right, then left, before coming to a stop. Maesa moved the compass. The pointer remained fixed unwaveringly on the desert.

‘Success?’ said Shattercap.

‘Success,’ said Maesa in relief.

Daylight receded from recollection. Shifting dunes crowded the mind as much as the landscape, and Maesa put all his formidable will into remembering who he was, and why he was there. Had he not, his sanity would have faded, and he would have wandered the desert forever.

Time without day loses meaning. The compass did not move from its position. Hours or lifetimes could have gone by. The desert landscape changed slowly, but it did change. Maesa came out of his fugue to find himself looking down into a gorge where shapes marched in two lines from one horizon to another. One line headed deeper into the desert and the realm’s edge, the other oppositely towards the heartlands of Shyish.

The sight was enough to shake Maesa from his torpor. Shattercap stirred.

‘What is it?’ asked Shattercap. His voice was weak.

‘Skeletons. Animate remains of the dead,’ said Maesa. The percussive click of dry joints and the whisper of fleshless feet echoed from the gorge’s sides. Purple starlight glinted from ancient bone.

‘What are they doing?’ said Shattercap.

‘I have no idea,’ said Maesa. ‘But we must cross their march.’

‘Master!’ said Shattercap. ‘Please, no. This is too much.’

Maesa urged Aelphis on. The great stag was weary, and stumbled upon the scree. Stones loosened by his feet sent a shower of rock before him that barged through the lines of skeletons and took two down with a hollow clatter. The skin of magic holding the skeletons together burst. Bones scattered. Like ants on their way to their nest, the animates stepped around the scene of the catastrophe, and continued on their silent way.

‘Oh, no,’ whimpered Shattercap.

‘Be not afraid,’ said Maesa. ‘They see nothing. They are set upon a single task. They will not harm us.’ He drew Aelphis up alongside the line, and rode against its direction. The skeletons heading outwards marched with their arms at their sides, but those going inwards each held one hand high in front of eyeless sockets, thumb and forefinger pinched upon an invisible burden.

Shattercap snuffled at them. ‘Oh, I see! I see! They carry realmstone, such small motes of power I can hardly perceive them. Why, master, why?’

‘I know not,’ said Maesa, though the revelation filled him with unease. Nervously, he checked his compass, in case the undead carried off that which he sought, but the compass arrow remained pointing the same direction as always. ‘I have no wish to discover why. Few beings could animate so many of the dead. We should be away from here.’

They left the name unsaid, but it was to Nagash, lord of undeath, Maesa referred. To whisper his name would call his attention onto them, and in that place Maesa had no power to oppose him.

‘Come, Aelphis, through the line.’

The king of stags bounded through a gap. The skeletons were blind to the aelven prince. With exaggerated, mechanical care, they trooped through the endless night, bearing their tiny cargoes onwards.

They passed several skeleton columns over the coming days. Always, they marched in two directions, one corewards, the other to the edge. They followed the lie of the land and, like water, wore it away with their feet where they passed, forming a branching of dry tributaries carrying flows of bone. Not once did the skeletons notice them, and soon the companions’ crossing of the lines became routine. The compass turned gradually away from their current path. By then notions of edgewards and corewards had lost all meaning. They knew the direction changed simply because they found themselves coming against the skeleton columns diagonally, then, as the compass shifted again, walking alongside them to the deeper desert. For safety’s sake, Maesa withdrew a little from the column the compass demanded he follow, shadowing it at a mile’s distance. Time ran on. The line of skeletons did not break or waver, but stamped on, on, on towards Shyish’s centre, each step a progression of the one behind, so the skeletons were like so many drawings pulled from a child’s zoetrope.

Some time later ¬– neither Maesa nor Shattercap knew how long – they witnessed a new sight. In a lonely hollow they spied a figure. On impulse Maesa turned Aelphis away from their route to investigate.

A human male squatted in the dust, a prospector’s pan in one hand. From the other he let a slow trickle of sand patter into the pan, then sifted it carefully around the pan while croaking minor words of power. Sometimes he would take a speck of sand out and put it into something near his feet. More often he would tip the load aside.

‘Good evening,’ said Maesa. It was dangerous approaching anyone in the wastes, but even the prince, who had spent solitary decades in his wandering, felt the need for company.

‘Eh, eh? Evening? Always night time. What do you want?’ said the man. He did not look up from his work.

Maesa saw no reason to lie. ‘I seek the life sands of my lost love. I hope to bring her back, and be with her again.’

‘Mmm, hmmm, yes. Many come here for the realm sand, the crystallised essence of mortal years,’ said the necromancer, pawing at the ground. He mumbled something unintelligible, then suddenly looked around, eyes wide. His skin was pallid. A peculiar smell rose from him. ‘You must be a great practitioner of the arts of necromancy to attempt to find a particular vein, though I doubt it. I never met an aelf with a knack for the wind of Shyish. But I, Qualos the Astute, necromancer supreme, I will have my own life soon bottled in this glass! By reversing it, I shall live forever. I alone have the art to exploit the Sands of Grief, whereas you shall fail!’ He chuckled madly. ‘What do you think of that?’

‘It is most impressi

ve,’ said Maesa.

The smile dropped from Qualos’ face, his eyes widened. ‘Oh, you best be careful! He doesn’t like it when souls are taken! You take the one you’re looking for, even a part, and he’ll come for you. He’ll not let you be until your bones march in his legions and your spirit shrieks in his host.’ He looked about, then whispered. ‘I speak of Nagash.’

The whisper streamed from his lips and away over the dunes, growing louder the further it travelled. Thunder boomed far away. Aelphis shied.

‘Not I, though. I have this! Within is my life! My soul is none but my own.’ He held up the bottom bulb of an hourglass. The neck was snapped, the top lost. The glass was scratched to the point of opacity. No sand would run in that vessel, unless it was to fall out.

‘I see,’ said Maesa neutrally.

‘The man is mad!’ hissed Shattercap.

‘Just a few grains more, then I will be heading back,’ said Qualos. ‘All the peoples of Eska will marvel at my feat!’ he said. He licked his lips with a tongue dry and black as old leather. ‘I don’t think you can do it, not like me.’ He cradled his broken glass to his chest.

‘We shall see,’ said Maesa.

‘Well, on your way!’ said the necromancer, his face transformed by a snarl. ‘You distract me from my task. Get ye gone.’

Aelphis plodded slowly by the man. As they passed him, Maesa glimpsed white shining inside his open robes. Shattercap growled.

Qualos’ ribs poked through desiccated flesh. Splintered bone trapped a dark hole where his heart had beaten, now gone.

‘He is dead!’ whispered Shattercap.

‘Yes,’ said Maesa.

Shattercap scrambled across Maesa’s shoulders to look behind.

‘You knew?’

‘Only when he spoke,’ admitted Maesa. ‘I thought him alive, at first.’

‘Should we not tell him?’ asked Shattercap.

‘I do not think it would make any difference, and it may put us in danger. His fate is not our business. The lord of undeath has him in his thrall. A cruel joke.’

Maesa directed Aelphis back upon their course and rode for a while. When he was sure they were out of sight of Qualos, Maesa pulled out Ghyran’s bottled life and regarded it critically.

‘The lack of this, however, is a cause for concern. There is enough for a few more days,’ he said. He looked towards the centre of Shyish, estimating the ride to more hospitable lands. ‘No more than that.’

‘What do we do when we run out?’ whimpered Shattercap.

Maesa would not answer.

Maesa and his companions were dying. Not a sharp blade-cut end, but the slow drip of souls weeping from broken hearts.

Grey dunes rolled away to chill eternities. Aelphis stumbled up slopes and down slip faces, his antlers drooped to his feet. Maesa swayed listlessly in the saddle. Shattercap was silent. A few drops of Ghyran’s life-giving waters remained to sustain them. They would have to return soon, or they would die.

At the same time, they grew hopeful. Increasingly in the dust they saw glittering streams of coarse grains of green, black, amethyst and other gemstone colours. These were realmstones of Shyish ¬– life sands, each streak on the dunes the crystallised essence of a life, a grain for every week or so. Maesa looked at his compass often, hoping against hope that the needle would turn and point to one of the deposits, but he was disappointed. The needle aimed towards the horizon always. None of the coloured streaks were Ellamar’s mortal days.

And then, the miraculous occurred. After what felt like years, and could have been, the needle on the compass twitched. Maesa stared dumbly at the device cupped in his hands. The needle was moving, swinging away from their line of travel.

‘Shattercap!’ said Maesa, his voice cracked from days of disuse.

‘Master?’ replied the spite, a breath of words no louder than the whisper of the windblown sand.

‘We approach! We are near!’

Maesa spurred Aelphis into life. Huffing wearily, the king of stags lumbered into a trot.

‘To the right, Aelphis! There!’ said Maesa, intent upon the dial.

Their path took them closer to the line of skeletons. At last, the source of the animates’ burdens became apparent. Where realmstone gathered most thickly, a depression had been carved.

Within the bowl of a great quarry, the two lines of skeletons joined into one. They entered, looped round, bent without slowing to peck at the sand, then walked around the back of the bowl and thence out again, carrying their dot of treasure away to their master. In the dim starlight, Maesa spied many such pits, some worked out, some alive with the flash of dead bones.

A moment of horror gripped him. If Ellamar’s sands were in one of those pits…

Relief came from the compass. It span a little to the left, then as Aelphis followed, to the right. The compass rotated slowly around and around. Maesa brought Aelphis to a halt and slid from his back.

Sand shifted under his feet. Rivulets of it ran from the dunes’ sides to fill his footsteps. The grey dust comprised the lesser part of it, much was realmstone. Many colours were mingled there. Many lives blended.

The prince stooped low, the compass held to the sand. By lifting individual grains to the compass rose and watching its spin, he ascertained that Ellamar’s life was of an indigo hue. One grain set the compass twirling sharply. A handful made it blur.

‘Fitting,’ he said. ‘Indigo was her favourite colour.’ He took out the last of the life water, and roused the spite. ‘Shattercap.’

‘Good prince?’

‘We shall finish this. We shall need all our strength. The servants of Nagash will come.’ He took a sip, gave a drink to Shattercap, and then tipped the last of the water into Aelphis’ mouth. The stag huffed and stood taller as vitality returned.

‘Help me. Pluck up this indigo sand.’ He drew out the hourglass from his saddlebags and placed it on the desert floor. He opened up the lid. ‘Fill it up. Carefully. Not one other grain, only hers.’

When lowered to the sand, Shattercap mewled. ‘It burns me, master!’

‘Bear the pain, and you shall be four steps closer to freedom,’ said the prince sternly. ‘Hurry!’

Together the aelf and spite worked, fastidiously plucking single grains of the glittering sand from the dust and depositing them in the hourglass.

The bottom bulb was almost full, and the grains becoming harder to sift from the rest, when a piercing shriek rose over the desert.

Shattercap’s head whipped up. His hands opened and closed nervously.

‘Master…’ he whimpered. ‘We are noticed.’

Another shriek sounded, then a third, each one nearer than the last. The ceaseless, gentle wind of the desert gusted fiercely.

‘Fill it, spite!’ commanded Maesa. He drew the Song of Thorns. The woody edge of the living sword sparked with starlight. ‘Get it all. I shall hold them back.’

Howling with outrage, a wraith came flying over the ridge of a nearby dune. It had no legs, but trailed streamers of magic from black robes in place of lower limbs. Its face was a skull locked into a permanent roar. Its hands bore a scythe. This, unlike the aethereal bearer, was solid enough, a shaft of worm-eaten wood and a blade of rusted metal with a terrible bite. Other wraiths came skimming over the sands, their corpse-light shining from the tiny jewels of other creature’s lives.

The first wraith raised its weapon, and bore down on the prince. Moving with the grace native to all aelves, Maesa sidestepped and with a single precise cut, sliced the spirit in two. It screamed its last, the shreds of its soul sucked within the Song of Thorns. Another came, swooping around and around Aelphis and Maesa before plunging arrow-swift at the prince. Maesa was faster, and ended it. The Song of Thorns glowed with the power of the stolen spirits.

More wraiths were coming. A chorus of shrieks

sounded from every direction. The undead burst from the sand, they swooped down from the sky. The watchdogs of Nagash were alert for thieves taking their master’s property, and responded to the alarm with alacrity.

‘Quickly, Shattercap!’

Maesa slew another, and another. The Song of Thorns was anathema to things such as the wraiths, but there were hundreds of them gathering in a tempest of phantoms. The spite scrabbled at the ground, his earlier finesse gone as he shovelled Ellamar’s life sands into the glass.

‘Be careful not to mix the grains!’ the prince shouted, cleaving the head of another wraith from its owner.

‘I am trying!’ squeaked the spite.

‘I cannot fight all these things,’ said Maesa. He was right. Now the wraiths saw the danger the Song of Thorns posed, they turned their attacks against Aelphis and Shattercap, and it took all of Maesa’s skill to keep them from harm. Aelphis reared and pawed at the wraiths, but all he could do was deflect their weapons from his hide. When his hooves hit their bodies, they passed through, leaving wakes of glowing mist.

‘I have it all!’ said Shattercap, ducking the raking hand of a wraith. He slammed closed the lid atop the hourglass.

‘You are sure? You have checked the compass?’

‘Yes!’ squealed Shattercap.

The prince danced around the stag, snatching up hourglass and compass in one hand while killing with the other. Shattercap leapt from the sand to the prince’s arm. Maesa jumped onto the back of the stag, cutting away the head of a scythe in mid-air, then reversing his stroke as he landed in the saddle to render another phantom into shreds of ectoplasm.

Aelphis reared. Maesa slashed from left to right. Braying loudly, the stag leapt forward.

Invigorated by Ghyran’s waters of life, Aelphis ran as fast as the wind. The wraiths set up pursuit, and more streamed from the depths of the desert to join them. Maesa slew all that came against him. He cried out when a scythe blade nicked his arm, numbing it with the grave’s chill. The wraiths screeched to see his discomfort and they closed in for the kill, but Maesa yelled the war cries of his ancestors and fought on.

The Red Feast - Gav Thorpe

The Red Feast - Gav Thorpe The Siege of Greenspire - Anna Stephens

The Siege of Greenspire - Anna Stephens Fangs of the Rustwood - Evan Dicken

Fangs of the Rustwood - Evan Dicken Blacktalon - When Cornered - Andy Clark

Blacktalon - When Cornered - Andy Clark Acts of Sacrifice - Evan Dicken

Acts of Sacrifice - Evan Dicken Obsidian - David Annandale

Obsidian - David Annandale A Dirge of Dust and Steel - Josh Reynolds

A Dirge of Dust and Steel - Josh Reynolds The Sands of Grief - Guy Haley

The Sands of Grief - Guy Haley The Book of Transformations - Matt Keefe

The Book of Transformations - Matt Keefe Warriors of the Chaos Wastes - C L Werner

Warriors of the Chaos Wastes - C L Werner Strong Bones - Michael R Fletcher

Strong Bones - Michael R Fletcher Sepulturum - Nick Kyme

Sepulturum - Nick Kyme The Witch Takers - C L Werner

The Witch Takers - C L Werner Gotrek & Felix- the Third Omnibus - William King & Nathan Long

Gotrek & Felix- the Third Omnibus - William King & Nathan Long A Tithe of Bone - Michael R Fletcher

A Tithe of Bone - Michael R Fletcher Reflections in Steel - C L Werner

Reflections in Steel - C L Werner Masters of Stone and Steel - Gav Thorpe & Nick Kyme

Masters of Stone and Steel - Gav Thorpe & Nick Kyme Gotrek & Felix- the Second Omnibus - William King

Gotrek & Felix- the Second Omnibus - William King Valdor- Birth of the Imperium - Chris Wraight

Valdor- Birth of the Imperium - Chris Wraight The Bone Cage - Phil Kelly

The Bone Cage - Phil Kelly Gotrek & Felix- the First Omnibus - William King

Gotrek & Felix- the First Omnibus - William King The Dance of Skulls - David Annandale

The Dance of Skulls - David Annandale Gloomspite - Andy Clark

Gloomspite - Andy Clark The Deeper Shade - C L Werner

The Deeper Shade - C L Werner Spear of Shadows - Josh Reynolds

Spear of Shadows - Josh Reynolds Gotrek - One, Untended - David Guymer

Gotrek - One, Untended - David Guymer Gotrek & Felix- the Fourth Omnibus - Nathan Long

Gotrek & Felix- the Fourth Omnibus - Nathan Long Gods' Gift - David Guymer

Gods' Gift - David Guymer Blood Gold - Gav Thorpe

Blood Gold - Gav Thorpe Slaves to Darkness 03 (The Heart of Chaos)

Slaves to Darkness 03 (The Heart of Chaos) Hamilcar- Champion of the Gods - David Guymer

Hamilcar- Champion of the Gods - David Guymer Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood And Steel)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood And Steel) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (what price vengeance)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (what price vengeance) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood of the Dragon)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood of the Dragon) Ursuns Teeth

Ursuns Teeth The Blackhearts Omnibus (Tainted Blood)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (Tainted Blood)![Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/09/daemon_gates_trilogy_01_day_of_the_daemon_preview.jpg) Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon]

Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon] The Blackhearts Omnibus (The Broken Lance)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (The Broken Lance) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood Money)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood Money) The Blackhearts Omnibus (Hetzaus Follies)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (Hetzaus Follies) Warhammer Red Thirst

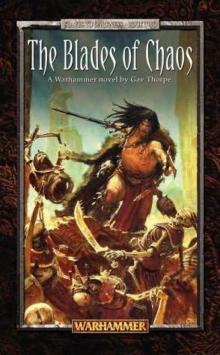

Warhammer Red Thirst Slaves to Darkness 02 (The Blades of Chaos)

Slaves to Darkness 02 (The Blades of Chaos)