The Red Feast - Gav Thorpe Read online

Page 2

Years?

Longer?

It was part of his cursed memory that he recalled little of what had happened in his long life, yet his mind was full to breaking with images of what he was sure would come to pass.

More than sure. His entire existence revolved around the fact. He had been set upon the world to make it so. He was the recorder of the future but also its catalyst. He knew this because he was always in his dreams. If somebody else had been marked to usher in the next age, they would have been dreaming those dreams instead.

He replaced the matting camouflage and squeezed through to the opening of the cave. Beneath a rock, in an alcove he had fashioned himself, his weapons and armour waited for him. They were scraps pieced together from corpses the beasts had left. He could smell the dried blood on them, a scent that seemed so much stronger in his nostrils of late.

There was so little of his wasted body left that the vambraces were barely more than studded tubes of leather on him. He could not find a breastplate that sat on his sunken chest and so instead he pulled on a thick harness with a small plate of iron nestled over his heart. He did not need extra weight to slow him – speed and wits served him better in his task – so he left the coif and simple round helm in their hiding place.

He looked at the spear, snug in the crack beside the main cave opening, but again decided it would be more of a hindrance. Instead he removed a dagger as long as his forearm from beneath the helm and mail, tying its belt around a waist pot-bellied in comparison to his spindly limbs.

Thus prepared, he stole to the mouth of the cave, checked the clearing outside and stepped out into the light of day.

CHAPTER TWO

Outside, Athol stopped in the shadows for a few moments. The season of Hotwind had only just started and it had been thankfully cool by comparison to previous seasons. When the winds turned and brought the north-burn the air would be like a furnace draught, its movement doing nothing to ease the stifling heat, the dryness stealing the moisture from the eyes and mouth. Shielding his eyes, he glanced up. Broad-winged scavenger birds circled on the hot air just below scant clouds, keen eyes searching the scrubland around the royal city.

The city was not so grand as the name suggested, of little comparison to the stone edifices raised by the likes of the Bataari and Aspirians, or the lifetombs of the Golvarians. A few hundred tents was miniscule when measured against the mighty duardin stronghold at Vostargi Mont. The capital of the Aridians lacked even the strength of the fortified wooden settlements of the other tribes with which they shared the Flamescar Plateau. Even so, it had one great strength the others could not match; it could move across the plains to seek water and verdant growth. Within the turn of a day, the whole of the royal city could be packed upon wagons pulled by gargantuan beasts known as whitehorns, akor in the tongue of the Aridians. Should the winds veer, a river dry or a herd migrate, the whole of the Aridian tribe could adapt, the royal city and its satellite settlements travelling for days on end until they found a new home.

For thirty days now the capital had not moved. Athol was no windwatcher, but it seemed that the mild weather would not hold for much longer. The watercourse that snaked through the centre of the tent city would run low and the whitehorns would move on, heading to cooler climes in the east and south. When that happened, the Khul would follow, for even as the Aridians followed the herds that brought them prosperity, so too did the Khul shadow the Aridians, who paid in milk, meat and hides for their blade-hands. A greedy Bataari thief was of little threat, but when the herds moved the Khul would be needed, their presence dissuading raiders from other tribes.

‘A disappointment.’

Athol looked around, recognising the voice of Khibal Anuk, the Prophet-Queen’s older half-brother. He stood in the shelter of the door-awning, fingers hooked into the thick belt that bound tight around his considerable waist. A small hammer pendant hung from a gold chain about his neck, the symbol of his calling.

‘What’s that, Sigmar-tongue?’ said Athol. He used the honorific out of respect for the Aridians’ traditions, though he cared little for Sigmar himself.

‘No trial by arms today,’ explained Khibal Anuk. ‘I had thought to see you use that spear.’

‘It would have been little spectacle,’ Athol assured him. ‘His champion will provide a better contest, I am sure.’

Khibal Anuk nodded and stroked his stubbled chins.

‘You like to fight?’

‘I was born to fight – it isn’t a question of what I like or dislike,’ Athol replied. He brandished his spear. ‘Does this like to slay, or is it simply what it does?’

‘You are not an inanimate object, Athol. You have feelings.’

‘I do, and I share them with my wife and son.’ Athol glanced away, his thoughts drawn to the distant encampment where his family waited for his return. ‘The queen claims only my blade-arm.’

‘You would have been at home at the Red Feast. Days of challenges and combat between the tribes, settled by champions like you.’

‘I know of it. I was in the entourage of my uncle when he attended as our champion, back when I was a youngster. He killed five men and women to defend the honour of our people.’ Athol frowned. ‘You speak of the Red Feast as a thing that has passed, and there has not been one called since we travelled to the gathering at Clavis Volk.’

‘The tribes settle their differences in other ways now, through the wisdom of Sigmar.’ Khibal Anuk touched a hand to his sacred amulet. ‘Better to be united than divided, and settle with peace what once was settled by war.’

‘The Red Feast existed to avoid war, I thought. To give the tribes a way to fight without butchering each other and destroying their homes. A better way to keep their honour.’

‘If one dies or a hundred, is honour worth killing or dying for?’

‘You seem troubled, Sigmar-tongue.’ Athol planted his spear in the dry earth and took a step towards the priest. ‘I hope my decision to accept the trial of arms did not displease the Prophet-Queen.’

‘Oh, I am quite sure she agrees with your course of action. She would not have offered the choice if she did not.’

‘If she had ordered me to fight the man’s champion, I would have done so.’

‘She is the Prophet-Queen. By rights she should have made Williarch fight. She must obey the law, after all, and he had not followed it.’ Khibal Anuk shrugged. ‘But that’s not what has troubled me. There have been a few members of the court that have suggested we sever our relationship with the Khul.’

‘I see. Does Humekhta know that you speak to me?’

‘Do not be alarmed. It is just whispers – I’m sure they fall on deaf ears. My half-sister knows the value of the Khul, even if others do not.’

‘Why? Both our tribes have benefited from the partnership.’

‘They speak of being beholden to outsiders, of our sword arms growing weak beneath the shield of the Khul.’

‘Your warriors are trained by us. They have never been better.’

‘I think that is part of the problem, Athol. It has been three generations since your people came to the lands of Aridian. Greedy minds forget how vulnerable they were before. Now we can fight for ourselves, they think. They see the price paid for your company and wonder if it is necessary.’

‘Perhaps you can defend yourselves.’

‘For a while. But the name of the Khul is a surer ward against attack than any number of our own soldiers.’ Khibal Anuk clasped his hands, almost resting them on his prominent gut. ‘You protect us doubly so. The very threat of fighting the Khul keeps our rivals’ hands from their sword hilts.’

He shifted his weight from foot to foot and back again, eyes regarding Athol closely.

‘Speak plainly what gnaws at your ear, Sigmar-tongue,’ Athol told him. ‘I will not pass on what you say to any other.’

‘It might be necessary to prove the worth of the Khul again. A reminder to those with short memories.’

&n

bsp; ‘I don’t understand what you think I can do.’

‘The peace we enjoy is a lie, Athol. You know it. We will be tested again, as soon as the herds thin, or when the hot wind blows long. It is in the nature of our people to settle matters with aggression, but a few years of bounty have dulled that temper. I am worried that without a… display of your people’s vigour the voices that question your presence will grow bolder and louder.’

‘You want me to start a fight? Wage a war?’

Khibal Anuk coughed nervously and gestured for Athol to keep his voice low.

‘Not start a war, no. Of course not. But should our enemies decide to test the queen’s mercy, it might go well to make an example of them. To show what happens when the anger of the Khul is stirred.’

Athol remembered that he was speaking to a high member of the court and held back the first thought that occurred – that should the full wrath of the Khul be slipped, the Aridians would be swept away by that unleashed storm. It would serve no purpose to alienate him.

‘I will remember what you have said, Sigmar-tongue. I am sure there is wisdom in your words.’

The Sigmar-tongue said nothing more but laid a hand on Athol’s arm before stepping back into the queen’s tent. Athol waited there for a few moments more, agitated by the priest’s words as he stared into the shadowed interior. He had no reason to distrust Khibal Anuk, but the Sigmar-tongue had never before tried to involve Athol in courtly politics. The champion had been robust in keeping himself clear of such entanglements and was annoyed that the priest seemed to be trying to draw him into the unfamiliar battleground.

He retrieved his spear and headed out into the tent city, sun gleaming on his armour as he passed between the rows of brightly coloured canvas structures. The respectful call of nakar-hau followed him along the streets, which he met with a raise of his weapon or nod of the head.

Spear-carrier. A simple phrase but one that conveyed heavy connotations for the Aridians. He was the bearer of the Prophet-Queen’s honour, responsible for protecting her reputation even as her personal guards shielded her body. In deed he was an extension of the queen, his actions reflecting upon her. It was no surprise that, even after three generations of service by the Khul, there were still some elements within Aridian society that considered it a dishonour for the nakar-hau to be an outsider.

He remembered his great uncle, the first to swear to the line of the Prophet-Monarchs, and how Orloa described the day he had bent his knee to the ruler of another tribe. It had brought peace, an end to fighting that the Khul had waged for two generations before. It was acceptance of a sort, not only by the Aridians but also the other tribes of the Flamescar. The Khul had both proven their martial prowess and earned the respect of the hardy plains people.

The smell of the akor pens grew stronger as he reached the outskirts, mixed with the musk-stench of the smaller noila the Aridians used as personal mounts. He did not turn towards the corrals but passed the last ring of tents on foot, for the Khul did not ride. They could march for days on end, or run for a full day and still fight a battle at the end of it. Steeds were simply more mouths to feed.

He walked slowly, the sun setting to his left. He followed the slow-flowing river towards the camp of his people, his thoughts weighing more heavily than the spear on his shoulder.

Braziers encircled the camp, warding away the starlit night. The clatter of pots being washed and soft lullabies greeted Athol, easing him back into the embrace of his people. Here there were no grand pavilions and garlanded streets of colourful tents, simply rows of neat, plain canvas sheets weighted on one end with rocks, held up by poles cut from the stubby trees of the plateau. It was shelter enough, a few windbreaks erected for the small cooking fires, the bedrolls of the inhabitants snug in the lowest parts of the bivouacs.

He stopped at the outermost line of shelters and lowered to one knee. He carefully placed his spear on the ground and, using his now free hand, scooped up a small handful of dirt. Raising it to his lips, he kissed his knuckles and let the dirt scatter from his palm, before drawing a smudge down his forehead with the grime on his thumb, smearing dusty red through the sweat.

Athol waited, taking in slow lungfuls of the warm air.

Eventually a figure emerged from the darkness to the right, a short stabbing blade in her left hand, a buckler held in the other. Her pale hair was stained red, hanging in a single braid across her shoulder, as was Khul tradition. In the shimmer of firelight her sharp cheeks cut shadows on her face until she stepped in front of the braziers and her features were lost in darkness.

‘Who stands upon the border of the Khul?’ she asked quietly, standing between Athol and the tents, weapon and buckler raised.

‘Athol Khul, son of Norod Khul.’

‘You are seen and welcomed. Take up your weapon, Athol Khul.’ He did so, and extended his other hand, palm outwards. The sentry touched the pommel of her sword to his palm and smiled. ‘I am glad you have returned to us.’

‘There was no trial today, Anitt,’ he told her with a sigh. ‘I must return in two days.’

‘There’s always another trial, Athol. Your son is asleep, and my sister is waiting for you by the Last Forge.’ She slapped him on the behind with the buckler as he stepped past. ‘Run along to your family, son-of-Khul.’

He strode with renewed purpose between the bivouacs, heading towards the glow of the Last Forge at the heart of the camp. A few of his tribes-kin looked up at his passing and exchanged greetings, as they sat around their small firepits finishing their meals, or sang quiet songs to the slow beat of palm drums. A few threw bones or whittled at wood, while others wove brightly coloured fabric from threads hanging on handlooms.

It seemed peaceful, but Athol also saw the sword or dagger, spear or axe, that was on the belt or within the reach of every adult in the camp. Each wore at least a collar of mail or vambraces and greaves, some heavily clad in breastplate and more. They moved without noticing the extra encumbrance, raised to treat their armour as others would their normal clothes. Shields were propped up against the poles holding up the shelters or hung from loops of rope stitched into the underside of the canvas. Should one of the sentries patrolling the extent of the light at the camp’s edge raise the alarm, three thousand warriors would be ready to fight within a few heartbeats.

Ahead he could make out a group of silhouettes against the constant gleam of the Last Forge’s light, sitting on low stools in front of its open grate. Even as he thought he made out the topknot of Marolin, his wife, a voice called his name behind, causing him to turn. Emerging from between two tents, a figure shorter but broader than Athol approached.

‘Korlik.’ Athol held out his palm but the Khul leathermaster ignored the gesture of greeting.

‘Nice walk, eh?’ the man said. Athol could smell fermented whitehorn milk on his breath and his tone was belligerent.

‘Nice enough.’ The spear-carrier was about to continue towards the Last Forge but a grunt from Korlik stopped him. ‘What do you want?’

‘Come for a drink, queen’s champion.’ Korlik waved a jug, the sparse remains of its contents sloshing inside. ‘We’ve got some news.’

‘I’m to see Marolin. Whispers travel fast. She’ll know I’m back.’

‘She’ll wait, I’m sure. We want to talk to you.’

‘Who’s “we,” Korlik?’ Athol glanced over his shoulder at the outline of his wife and the others, a sigh escaping. He waved for Korlik to show him the way. ‘Fine, but this had better not take long.’

The leatherworker stomped off between the rough tents, heading towards the area near the river where the regular smithies, tannery and other workshops were located. The pleasant smell of roasted meats and stewed tubers was replaced by the stench of the crafters’ trades. It hung on the warm air like a fog, clinging to Athol’s nostrils as he followed Korlik into a broader opening alongside the river. The babble of voices he had heard on approaching fell silent. A fire had been heaped up in the r

ough ring, and around it on logs and stumps sat thirty or so tribesfolk, all of them Athol’s age or older.

‘What’s this?’ he asked. ‘A council of would-be elders?’

His comment was met without humour, the glint of the fire dancing in the eyes of his unexpected audience. Korlik emptied the last of his jug and tossed it to the flattened grass among a pile of others. He stooped to pick up a stoppered ewer and tossed it to Athol, who just about caught it in his free hand. The champion hooked his thumb into the handle but did not open the wax-sealed lid.

‘Take a drink,’ said Korlik. ‘You must have a thirst after your walk to the royal city and back.’

‘You’re drunk,’ Athol replied. ‘Maybe too drunk to fight?’

‘Too drunk to…?’ Korlik pulled himself straight and slapped a hand to the scabbarded tulwar at his thigh. ‘Is that what you think? You want to beat me, eh? Too drunk to fight! I’ll show you.’

‘Sit down, Korlik.’ The woman’s voice came from behind Athol but he recognised it immediately. He turned, a smile on his lips as Marolin strode into the firelight. Behind her were a handful of the other mothers. ‘Don’t say anything we’ll all regret.’

‘Your husband accuses me of breaking the law, Marolin, daughter-of-Khul. Drunk, he says!’

‘No man or woman shall be too drunk to fight,’ said Athol. He crouched and set the jug of skisk down at his feet. ‘That is the law.’

‘Fight who?’ The question came from Revvik, a woman a few years older than Athol, sat on a felled log to his left. She had lost her right hand in a battle against raiders, the missing appendage replaced with an angular bronze hook. It gleamed in the firelight as she scratched a scarred cheek with its tip. ‘The law says we must be ready in case of attack. Who’s going to attack us, Athol?’

‘Is that what this is about?’ said Athol. ‘It’s been a season since we last took to the field of battle and now you’re all bored.’

The Red Feast - Gav Thorpe

The Red Feast - Gav Thorpe The Siege of Greenspire - Anna Stephens

The Siege of Greenspire - Anna Stephens Fangs of the Rustwood - Evan Dicken

Fangs of the Rustwood - Evan Dicken Blacktalon - When Cornered - Andy Clark

Blacktalon - When Cornered - Andy Clark Acts of Sacrifice - Evan Dicken

Acts of Sacrifice - Evan Dicken Obsidian - David Annandale

Obsidian - David Annandale A Dirge of Dust and Steel - Josh Reynolds

A Dirge of Dust and Steel - Josh Reynolds The Sands of Grief - Guy Haley

The Sands of Grief - Guy Haley The Book of Transformations - Matt Keefe

The Book of Transformations - Matt Keefe Warriors of the Chaos Wastes - C L Werner

Warriors of the Chaos Wastes - C L Werner Strong Bones - Michael R Fletcher

Strong Bones - Michael R Fletcher Sepulturum - Nick Kyme

Sepulturum - Nick Kyme The Witch Takers - C L Werner

The Witch Takers - C L Werner Gotrek & Felix- the Third Omnibus - William King & Nathan Long

Gotrek & Felix- the Third Omnibus - William King & Nathan Long A Tithe of Bone - Michael R Fletcher

A Tithe of Bone - Michael R Fletcher Reflections in Steel - C L Werner

Reflections in Steel - C L Werner Masters of Stone and Steel - Gav Thorpe & Nick Kyme

Masters of Stone and Steel - Gav Thorpe & Nick Kyme Gotrek & Felix- the Second Omnibus - William King

Gotrek & Felix- the Second Omnibus - William King Valdor- Birth of the Imperium - Chris Wraight

Valdor- Birth of the Imperium - Chris Wraight The Bone Cage - Phil Kelly

The Bone Cage - Phil Kelly Gotrek & Felix- the First Omnibus - William King

Gotrek & Felix- the First Omnibus - William King The Dance of Skulls - David Annandale

The Dance of Skulls - David Annandale Gloomspite - Andy Clark

Gloomspite - Andy Clark The Deeper Shade - C L Werner

The Deeper Shade - C L Werner Spear of Shadows - Josh Reynolds

Spear of Shadows - Josh Reynolds Gotrek - One, Untended - David Guymer

Gotrek - One, Untended - David Guymer Gotrek & Felix- the Fourth Omnibus - Nathan Long

Gotrek & Felix- the Fourth Omnibus - Nathan Long Gods' Gift - David Guymer

Gods' Gift - David Guymer Blood Gold - Gav Thorpe

Blood Gold - Gav Thorpe Slaves to Darkness 03 (The Heart of Chaos)

Slaves to Darkness 03 (The Heart of Chaos) Hamilcar- Champion of the Gods - David Guymer

Hamilcar- Champion of the Gods - David Guymer Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood And Steel)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood And Steel) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (what price vengeance)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (what price vengeance) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood of the Dragon)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood of the Dragon) Ursuns Teeth

Ursuns Teeth The Blackhearts Omnibus (Tainted Blood)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (Tainted Blood)![Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/09/daemon_gates_trilogy_01_day_of_the_daemon_preview.jpg) Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon]

Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon] The Blackhearts Omnibus (The Broken Lance)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (The Broken Lance) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood Money)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood Money) The Blackhearts Omnibus (Hetzaus Follies)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (Hetzaus Follies) Warhammer Red Thirst

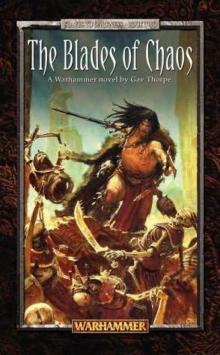

Warhammer Red Thirst Slaves to Darkness 02 (The Blades of Chaos)

Slaves to Darkness 02 (The Blades of Chaos)