Gloomspite - Andy Clark Read online

Page 5

They stood over the remains of Watchman Second Class Ulswell. Scraps of Watch uniform still clung to her ravaged form. White bone showed through a red and grey pulp of flesh and muscle. Half the watchman’s face was still recognisable, one eye staring up in glassy horror.

‘And she was found like this in the early hours, yes?’ asked Helena. Watchman Third Class Ilvik, the first watchman on the scene, nodded and looked nauseated.

‘A gang of urchins found her, captain. Came running straight to find a watchman. Eyes wide as saucers and half of ’em crying just with the sheer shock of it.’

‘And you say that when you got here there were insects on the body?’

Ilvik shuddered and shook his head in horror at the recollection.

‘Beg your pardon, captain, but that’s like saying there’s the odd skirmish on the Flamescar Peninsula. I get here and all I see is this sort of… squirming… in the dark, and I think well maybe she’s not dead, can’t be if she’s still moving can she? But the urchins won’t come any closer so I raise my lantern and take a proper look and I realise it’s not her that’s moving, its…’ Ilvik raised a clenched fist to his mouth for a moment, coughed, took a breath and continued. ‘It’s insects, captain. Hundreds of insects, some black and shiny as onyx, some all pale and see-through, and all of ’em just a tangle o’ too many legs and wavy…’ he mimed antennae with his fingers and looked at her helplessly.

‘And you believe that these insects, what, ate Watchman Second Class Ulswell?’ asked Helena, fighting to keep the note of incredulity from her voice. ‘I assume you mean that they were drawn to the body after it was dumped here, yes?’

Ilvik looked at her with frank dismay.

‘Captain, I’ll remember it until the day I pass on into Sigmar’s light. They were still eating her when I got here, and they didn’t scatter at my footsteps like they ought. No, they…’ he swallowed with a click. ‘Some of ’em broke off chewing on Ulswell and started scuttling towards me.’

Helena stood for a moment, watching Ilvik’s face to make sure she was not somehow being mocked. There was nothing but horrified sincerity in his haunted expression.

‘Well, they’re gone now,’ she said. ‘But we need to know where they came from and what they were, in case there is some infestation we must be–’

Grange gave a sudden bark of revulsion, causing Helena to jump as he took an involuntary step back. She followed his gaze and her eyes widened as she saw something come squirming out of Ulswell’s hollow rib cage. It was a millipede of some sort, but worm-white and bloated looking, its slimy hide slick with Ulswell’s blood. The thing moved on legs that were splayed and spider-like and beat a busy tattoo against the watchman’s ribs as it scuttled out into the light.

The insect kept coming, impossibly long and large, eliciting cries of horror and a frantic stir of movement from the watchmen. A scribe vomited noisily. Meanwhile, the insect slipped from inside Ulswell’s carcass like some obscene, chitinous rope. Feathery antennae waved as it reared up and turned its thumb-sized head towards the gathered watchmen. For a moment, Helena felt again the revolting caress of insectile legs moving over her sweat-slick skin.

Then came a loud bang that made her jump. The top few inches of the monstrous creature vanished, splattering in a viscous spray across the factory wall, and its body fell back, thrashing and flailing atop the mangled corpse before laying still.

Helena looked down at the smoking pistol in her hand. She hadn’t even been conscious of drawing it. Gulping a breath, she holstered the weapon.

‘Nobody touches these remains,’ she ordered. ‘We won’t be removing them for apothecary’s augury. We will be burning them, right here, right now. You–’ she began, pointing at Ilvik, but before she could continue she heard running footsteps pelting down the alley. Rainwater slapped under booted feet and echoed from the enclosing walls.

Helena and her companions turned to see a watchman running towards them. Helena frowned as she recognised the woman from Fountains Square. The watchman, in turn, pulled up short, no doubt startled by the array of horrified expressions in front of her. After a beat she collected herself and saluted.

‘Captain, you’d better come back to the square quickly, there’s been an incident.’

‘What now?’ barked Helena.

‘The vagrant you were speaking to, captain, Posver…’ the watchman trailed off, her eyes widening as she took in Ulswell’s corpse and the revolting carcass atop it.

‘Watchman,’ snapped Helena. ‘What about Posver? Why do you need me?’ The watchman’s eyes snapped back to her as though she had just remembered where she was.

‘Captain, about ten minutes after your conversation with him, Enwin Posver purchased a second bottle of drakesbreath from his usual vendor on Wagon Lane. I followed him as per your instructions, and he returned to the square. I expected… he… Captain, Posver began shouting about a moon, so loud and frantic that I moved to pacify him as he was alarming the city folk. Before I could reach him, Posver emptied the contents of the bottle over himself then lit it on fire. I rushed to him, pushed him into the fountain, but it was too late. He’s dead, captain.’

Helena shook her head in mute horror. She’d known poor Old Posver a long while and, though he had come out with some impressive rants in his time, she’d never seen him so much as raise a hand in violence, to himself or any other.

What did you see? she heard herself asking him again. Enwin, what’s coming? What did you see…?

Chapter Three

CLOUDS

Olt Shev pushed past a screen of ashenpine boughs. He stared through the rain, across a stretch of fuming marshland, at the city they had come to save.

Or warn.

Or fleece?

He wasn’t entirely clear on the details. Olt struggled with subtleties of the Azyrite languages, which shared only an ancient base root with his own Pyremouth Tribe dialect. Hendrick had definitely ordered the Swords of Sigmar to Draconium, though, Olt had made sure of that much when he rejoined the party south of Stonehallow.

Olt was tall and wiry, and if he was honest with himself only his scraggly brown beard stopped him looking about twelve kindlings of age. His spare frame was covered with tribal tattoos that depicted raging fire-deities and sigils of arcane warding, and all flowed into the screaming pyreskull design that covered most of his face beneath his short-hacked hair. He wore furs and leather armour scavenged from a dozen dead, wore a pair of curve-hafted axes at his belt that could be wielded or flung with equal ease, and bore a patchwork of scars and obsidian piercings across his flesh. In all, he was an alarming sight to the majority of civilised folk; there was a reason he had chosen to remain in his native wilds, rather than brave the small and fearful minds of Stonehallow.

‘No avoiding this place, though,’ he muttered to himself glumly. ‘Chief isn’t going to let me stay beyond the walls this time. Why these Heav’ners can’t learn to read their own maps I don’t know. They’d get lost in a sulphur swamp in a day without me, though.’

‘You underestimate us,’ came a voice from directly above, which made Olt jump and grab for his axes. He looked up, squinted, and relaxed as he made out the half-visible form of Aelyn crouched on a high bough. Her garb blended with the undergrowth to a degree that seemed almost supernatural. For all Olt knew, it was. He touched two fingers to the warding flame tattooed in the hollow of his throat, then to the heart-spark inscribed on his chest.

‘Careful with gestures like that, in there,’ said the aelf, pointing with her chin at the city ahead. Olt looked back at it, a long, curving wall forty feet high, made from iron and marble and painted with some oily treatment to ward off the acid rains spawned by the volcanoes that rumbled high above. Rooftops and spires and flags jutted above that wall. A hill rose towards the city’s centre with more buildings crowding its slopes and clinging to its crest.

‘Before the Heavensgates opened, I never seen more than a dozen or so buildings in one place,’ he grumbled to Aelyn. ‘Small tribes, high walls, sharp spears and everyone knew everyone else. What do you Heav’ners need so many buildings for anyway?’

‘Olt…’ said Aelyn.

‘I’ll wear my cloak, don’t worry,’ Olt replied. ‘Go tell the chief we’ve found it. And stop sneakin’ up on me!’ he called after Aelyn as she melted back into the canopy.

‘Stop making it so easy, then…’ her voice floated back to him.

Olt settled into the underbrush with a scowl and watched Draconium with wary eyes.

Metal glinted, the helms and speartips of guards patrolling the walls.

Lots of guards, he thought.

A wide waterway emerged through a heavy metal portcullis in the city wall, a broad roadway running alongside it, both cutting through the marsh and punching into the forest a few miles to Olt’s right. A few heavily laden barges sat on that waterway as though waiting to enter the city, but he noted that nothing was moving.

The brutish flanks of the volcanic Redspines marched away to the east and west, soon lost in a haze of sulphur-smoke and rain. Overhead, clouds were gathering thick and dark, thunderheads flowing down in waves from the north and piling up over the city. Lightning sparked in their depths. It reached crooked fingers down to jab at the mountainsides.

An uncomfortable tightness settled in Olt’s gut as he stared at the city. He glanced at the twin calderas that overlooked Draconium and offered up a silent prayer to their guardian spirits.

‘We get in there, we do what the chief wants, and we get out again,’ he said to himself, touching his warding flame again. ‘And we do it flickerswift.’

Hendrick stepped from the shadows of the forest eaves and scowled as the rain stung his bare scalp. The others emerged behind him: Romilla, their priest; Eleanora carrying her engineer’s tools; Borik with his cannon and Aelyn pacing whisp-light with bow in hand. At the rear, leaning heavily on his gnarled staff and clad in the black robes of a death wizard, came the elderly figure of Bartiman Kotrin.

‘Hood up, chief,’ said Olt, lurking beneath his heavy hide cloak. ‘Firemountains make the rain here bad. The imps in it’ll burn you if you give them the chance.’ Olt said something else in a dialect Hendrick didn’t understand, but he caught the tone of a curse all the same. The tribesman was not happy.

Rightly so, Hendrick thought. None of them was happy. Not with his brother gone. Not with him in charge.

‘Sigmar curse whatever deviltry was at work in those woods,’ said Romilla from behind him. ‘I can only assume the local priests failed to properly reconsecrate the ground, for surely the malice of the Dark Gods itself haunts the damned place.’

‘No malice,’ said Aelyn. ‘Why should the realms be any more accepting of our yoke than they are of our enemies’?’

‘Well, something in there hated us,’ retorted Romilla. ‘That was not an easy march.’

‘The bite on my foot still hurts,’ said Eleanora. ‘It was a spider that bit me, I think. I saw it and I think it must have been at least the size of my fist. It was horrible, but at least it scuttled off when I swatted at it. I’m sure I could make something that would repel those sorts of nasty biting creatures, maybe a spray or something that makes a sound they don’t like, but I’d need a proper workshop and some time. Hendrick, do you think there’ll be time for me to access proper workshop facilities in Draconium?’

‘Enough. All of you,’ said Hendrick. He closed his eyes and took a deep breath, letting it out slowly. ‘Hoods up and skin covered wherever possible. Stow your weapons, I don’t want to march up to the gates looking like a gang of killers. No matter what we actually are,’ he added to forestall any arch comments.

They did as he instructed.

‘Hendrick, I’ll only need a couple of days and–’

Romilla laid a hand on Eleanora’s arm, shook her head at the engineer with a gentle smile. Eleanora frowned, made a quick counting motion on the fingers of each hand, right then left, then pulled up the hood of her cloak and hunched her shoulders miserably against the rain.

‘Aelyn, what do you make of it?’ asked Hendrick quietly as the waywatcher came to stand alongside him.

‘Loaded barges idling outside a closed portcullis,’ she replied. ‘No foot traffic on the southward road. Lots of guards. Trouble.’

Hendrick gave a grunt of agreement. ‘Could be our warning comes a little too late,’ he said.

‘No, the storm still gathers,’ she replied. ‘We should be swift. You don’t need omens to feel there is something deeply wrong here.’

‘Let’s be about it then,’ he said, and set off for the distant city walls.

The marshes were easier to cross than Hendrick expected. Packed-earth pathways extended through them, some wide enough for carts to pass two abreast and patched where necessary with wooden planks. Smaller paths wound away towards scattered peat-diggers’ huts and shepherds’ lean-tos.

‘Looks like there are some folk unwilling to trade their independence for the protection of the city’s walls,’ commented Bartiman. His voice was deep and mellifluous for one who looked so wrinkled and old. It only matched his eyes, which sparkled impishly.

‘Fools. The realms are dangerous enough without eschewing what Sigmar offers,’ said Romilla.

‘Where they are, though?’ asked Olt. ‘I see the homes, but not the people or their herds.’ Hendrick saw their scout was right; no whisp of smoke rose from any sod hut, no herd-beasts chewed at the tough grass of the marshes.

‘Maybe not such idiots after all,’ he said, taking in the full scale of Draconium’s southern wall. It ran from one craggy mountainside to the other, its end-towers carved right into the craggy rockfaces. The wall blocked off the pass entirely and loomed like a menacing shadow over the fringe of the marsh.

Mud squelched underfoot as Hendrick crossed into the long shadow of that wall, over which loomed the smouldering volcanoes and, above them, a slowly massing immensity of black storm clouds. For a moment he felt a claustrophobic sense of panic, as though the whole lot might come thundering down to bury him alive.

‘This is for your brother, coward,’ he muttered to himself. ‘Just get the job done.’

Ignoring Aelyn’s amber-eyed glance, Hendrick led his small mercenary band into the shadow of the wall, to where a wide and well-maintained roadway ran along its base. That road, he saw, ran off along the feet of the Redspines to the west, while to the east it passed before the wall’s formidable gatehouse, then slid in alongside the Hammerhal Canal and sped away southwards.

‘If we’d have come from the other direction, it would have been a much easier march,’ said Eleanora, counting on the fingers of her right hand, then her left, oblivious to Olt’s irritated glare. ‘When we get into the city I’m going to find a map of this region and see about buying it, so that we don’t make that sort of mistake again. And I’m going to get access to a workshop so that I can make my spider repeller.’

‘If we get into the city,’ said Borik. ‘Gate’s shut.’

Hendrick squared his shoulders and led the way along the base of the wall, ignoring the stares of curious guards who peered over the top. He stopped before the huge mass of the gatehouse and took a moment to study it. Two blocky towers of iron-banded marble flanked a deep-set archway with a drake’s head crest worked in relief above its keystone. An imposing portcullis closed off this end of the tunnel leading into the city, while further back he could see slab-like inner doors doing the job from the city side. Hendrick could feel the stares of dozens of guards upon him, but he remained silent, as did his followers as they clustered around him.

‘Good luck, friend,’ came a distant shout, and Hendrick glanced over to see one of the bargemen leaning on the rail of his craft. ‘We’ve been waiting out here in the rain for three cheff

ing days. City’s shut, and they’re more than happy to let my produce rot rather’n open the cheffing rivergate for five minutes.’

Hendrick turned back to the gate, made a show of considering the bargeman’s words and the lack of address from the guards on the ramparts above. Then he cleared his throat and strode up to the portcullis.

‘Hello, up there?’ Hendrick cried. It had been years since his temper had seen him ejected from the ranks of the Freeguild, yet he could still drum up that sergeant’s booming shout when he needed to. He saw shapes move behind the battlements, saw the tops of spears stir. No response. ‘We’ve come with important information for the rulers of your city,’ he tried. ‘We’ve a warning they need to hear.’

Still nothing. Hendrick let out a grunt of annoyance.

‘I’ll try knocking,’ he said.

Hendrick slid Reckoner from its back-scabbard, hefted the massive hammer and swung it at the portcullis. The weapon’s head connected with the iron bars hard enough to send numbing shocks up Hendrick’s arms. The clang of its impact rolled out like a flatly tolling bell. The bargeman’s delighted laughter sounded in its wake.

Bow strings hissed somewhere above, and half a dozen arrows feathered the ground around Hendrick’s feet.

‘Those were a warning,’ came a gruff voice from the battlements. ‘Piss off, baldy. Take your bandit friends with you.’ At his back, Hendrick heard the ratcheting clank of Borik engaging the mechanism of his rotary cannon. The duardin would now have it levelled at the battlements, Hendrick knew, and he was only too aware of how much damage it could do if Borik got the excuse to fire. Still, he waved a placating hand at his companion.

‘Stow the gun, Jorgensson, there’s a lot more of them than there are of us,’ he said, eliciting an unintelligible mutter from Borik. ‘I just wanted to get a conversation going. Now,’ he barked, turning his attention back to the half-seen figures atop the battlements. ‘I’m sure you’ve got your orders, but a good man lost his life getting this warning for you so why don’t you be good lads and lasses, stop holding us up and let us in so we can talk to someone in charge? We just want to deliver this message then we’ll be on our way and you can go back to hiding behind your walls.’

The Red Feast - Gav Thorpe

The Red Feast - Gav Thorpe The Siege of Greenspire - Anna Stephens

The Siege of Greenspire - Anna Stephens Fangs of the Rustwood - Evan Dicken

Fangs of the Rustwood - Evan Dicken Blacktalon - When Cornered - Andy Clark

Blacktalon - When Cornered - Andy Clark Acts of Sacrifice - Evan Dicken

Acts of Sacrifice - Evan Dicken Obsidian - David Annandale

Obsidian - David Annandale A Dirge of Dust and Steel - Josh Reynolds

A Dirge of Dust and Steel - Josh Reynolds The Sands of Grief - Guy Haley

The Sands of Grief - Guy Haley The Book of Transformations - Matt Keefe

The Book of Transformations - Matt Keefe Warriors of the Chaos Wastes - C L Werner

Warriors of the Chaos Wastes - C L Werner Strong Bones - Michael R Fletcher

Strong Bones - Michael R Fletcher Sepulturum - Nick Kyme

Sepulturum - Nick Kyme The Witch Takers - C L Werner

The Witch Takers - C L Werner Gotrek & Felix- the Third Omnibus - William King & Nathan Long

Gotrek & Felix- the Third Omnibus - William King & Nathan Long A Tithe of Bone - Michael R Fletcher

A Tithe of Bone - Michael R Fletcher Reflections in Steel - C L Werner

Reflections in Steel - C L Werner Masters of Stone and Steel - Gav Thorpe & Nick Kyme

Masters of Stone and Steel - Gav Thorpe & Nick Kyme Gotrek & Felix- the Second Omnibus - William King

Gotrek & Felix- the Second Omnibus - William King Valdor- Birth of the Imperium - Chris Wraight

Valdor- Birth of the Imperium - Chris Wraight The Bone Cage - Phil Kelly

The Bone Cage - Phil Kelly Gotrek & Felix- the First Omnibus - William King

Gotrek & Felix- the First Omnibus - William King The Dance of Skulls - David Annandale

The Dance of Skulls - David Annandale Gloomspite - Andy Clark

Gloomspite - Andy Clark The Deeper Shade - C L Werner

The Deeper Shade - C L Werner Spear of Shadows - Josh Reynolds

Spear of Shadows - Josh Reynolds Gotrek - One, Untended - David Guymer

Gotrek - One, Untended - David Guymer Gotrek & Felix- the Fourth Omnibus - Nathan Long

Gotrek & Felix- the Fourth Omnibus - Nathan Long Gods' Gift - David Guymer

Gods' Gift - David Guymer Blood Gold - Gav Thorpe

Blood Gold - Gav Thorpe Slaves to Darkness 03 (The Heart of Chaos)

Slaves to Darkness 03 (The Heart of Chaos) Hamilcar- Champion of the Gods - David Guymer

Hamilcar- Champion of the Gods - David Guymer Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood And Steel)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood And Steel) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (what price vengeance)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (what price vengeance) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood of the Dragon)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood of the Dragon) Ursuns Teeth

Ursuns Teeth The Blackhearts Omnibus (Tainted Blood)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (Tainted Blood)![Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/09/daemon_gates_trilogy_01_day_of_the_daemon_preview.jpg) Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon]

Daemon Gates Trilogy 01 [Day of the Daemon] The Blackhearts Omnibus (The Broken Lance)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (The Broken Lance) Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood Money)

Brunner the Bounty Hunter (Blood Money) The Blackhearts Omnibus (Hetzaus Follies)

The Blackhearts Omnibus (Hetzaus Follies) Warhammer Red Thirst

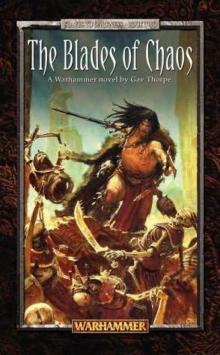

Warhammer Red Thirst Slaves to Darkness 02 (The Blades of Chaos)

Slaves to Darkness 02 (The Blades of Chaos)